WHAT IS RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS?

Written by Joshua Farragher

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disease that can have a progressive disabling effect to various joints in the human body (Firestein, 2003). It is characterised by pain, inflammation and swelling of the joint, cartilage and bone damage and autoantibody production (including rheumatoid factor) (McInnes & Schett, 2011).

Like other autoimmune diseases, RA involves the abnormal activity of the body’s immune system, whereby the immune response is targeted towards its own healthy tissue. In the case of RA, the immune system targets the outer lining of the joints, known as the synovial membrane, causing an increase in joint synovial tissue and ultimately pain and swelling (Aletaha et al., 2010).

RA more commonly effects smaller joints such as those within your hands and feet. Though this is not exclusive and larger joints such as hips and knees can also be affected (Aletaha et al., 2010).

There is currently no known cause for RA, however there have been several studies demonstrating correlations between genetic and environmental factors.

SYNOVIAL JOINT ANATOMY

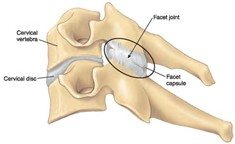

Synovial joints are the most common joint type within the human body. They are designed to allow us to move whereas non-synovial joints, such as roots of your teeth or joints between segments of the cranium, are usually designed for rigidity. Synovial joints consist of an articular capsule, articular cartilage and synovial fluid.

The synovial membrane (lining of the joint) exists as a layer of tissue within the joint capsule. It is a soft tissue that is continuous from the periosteum (outer surface layer of the bone) of the adjoining bones. Within the synovial membrane there is the joint cavity/space, filled with synovial fluid. The synovial fluid is produced by the synovial membrane and can be thought of as lubricating fluid to assist with frictionless movement of the joint. Within the synovial cavity also lies the adjoining bones outlined by articular cartilage.

Articular cartilage plays an important role in protecting the underlying bone whilst also reducing friction during movement and absorbing force. Articular cartilage is avascular and aneural, meaning there is no blood or nerve supply. Due to the absence of blood vessels, cartilage tissue has a slow turnover of its cells and therefore does not repair. Also, as there is no neural tissue, articular cartilage cannot provide any signals to your brain, therefore it cannot be a structural source of pain. However, the underlying bone is highly vascular and neural, as cartilage tissue degenerates less force absorption and friction during movement is translated to the underlying bone. Despite having no blood supply, cartilage tissue still requires a source of nutrients which comes from the synovial fluid that surrounds it. This is accessed through movement and load of the joint.

WHAT ARE THE SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS?

The symptoms of RA vary throughout the population; however, some common symptoms include (Aletaha et al., 2010):

- Joint pain and swelling; this may be accompanied with localised heat

- Stiffness and pain, particularly noted in the morning

- Similar symptoms presenting in other joints, usually the same or similar joints on opposite sides

The symptoms of RA are likely to occur without any defining injury or mechanism and can therefore seem to appear for no apparent reason.

DO I HAVE RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS?

A diagnosis of RA is made from a combination of physical examination, radiology and pathology tests.

Physical testing can include:

- Joint palpation to assess for painful areas of the joint

- Range of movement testing for stiffness/restriction

- Strength testing for weakness; likely due to pain inhibition

Pathology tests involve:

- Blood examinations for inflammatory markers

- Blood examinations for antibodies and other markers such as rheumatoid factor

Radiological testing usually involves an x-ray of the joint to assess for changes to articular cartilage, though this is rare in the early stages of the disease.

TREATMENT OF RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis is primarily managed by a rheumatologist. From a medical perspective, there are multiple forms of treatment and combinations of treatment due to the varying nature of the condition, as well as individual’s response to medication varies greatly.

Common medications for RA include (Smolen, Aletaha, Koeller, Weisman, & Emery, 2007):

- Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs)

- Biological DMARDs

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication

- Steroidal anti-inflammatory medicines such as prednisolone or corticosteroid injections

Overarchingly the research supports people staying physically active and eating a healthy diet. As with most auto-immune diseases, there is a significant negative impact that smoking can have on RA, therefore it is imperative people take active measures to stop smoking (Klareskog et al., 2006).

Staying active can vary enormously for each individual due to pain responses and individual preferences for exercise. Many people with RA commonly find when they try to increase their physical activity it results in increases in joint pain.

Management of RA commonly involves a multi-disciplinary approach. Physiotherapists play an important role in finding effective ways for each individual with RA to exercise (Hurkmans et al., 2011; Kavuncu & Evcik, 2004). Most commonly physiotherapists role in exercise for people with RA involves:

- Modifying biomechanical load through movement to allow for greater/longer participation in physical activity without significant increases in pain

- Building structured plans to progress muscle strength/endurance and increase joint load tolerance to allow for greater participation

If you recall the information from above that articular cartilage damage occurs in the latter stages of the disease, one of the main aims is to slow or minimise the impact RA has on this tissue. Articular cartilage gains its nutrients through movement and load to the joint, thus making it imperative to stay active to prevent unnecessary degenerative effects to cartilage.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

There are many sources for joint pain, leaving there to be a myriad of possible diagnoses. Excluding the conditions that often result from a sudden injury, some of the potential other diagnoses include (Alpay-Kanitez, Celik, & Bes, 2019):

- Osteoarthritis – localised degenerative changes to a synovial joint that result independently of systemic changes such as increases in blood inflammatory markers and rheumatoid factor as in RA

- Gout – a build-up of uric acid crystals within a joint as a result of high levels of uric acid in the blood

- Seronegative RA – similar symptoms to RA, however lacking rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP antibodies

- Psoriatic Arthritis – similar to RA, however lacking rheumatoid factor and have presence of psoriasis

- Infectious arthritis – usually only effects one joint and results in arthritic changes to a joint as a result of an infection from the synovial fluid or blood

REFERENCES

Aletaha, D., Neogi, T., Silman, A. J., Funovits, J., Felson, D. T., Bingham, C. O., 3rd, . . . Hawker, G. (2010). 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis, 69(9), 1580-1588. doi:10.1136/ard.2010.138461

Alpay-Kanitez, N., Celik, S., & Bes, C. (2019). Polyarthritis and its differential diagnosis. Eur J Rheumatol, 6(4), 167-173. doi:10.5152/eurjrheum.2019.19145

Firestein, G. S. (2003). Evolving concepts of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature, 423, 356-361.

Hurkmans, E. J., van der Giesen, F. J., Boonman, D. C. G., van der Esch, M., Fluit, M., Hilderdink, W. K. H. A., . . . Vliet Vlieland, T. P. M. (2011). Physiotherapy in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Development of a practice guideline. Acta Reumatológica Portuguesa, 36(2), 146-158.

Kavuncu, V., & Evcik, D. (2004). Physiotherapy in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Medscape General Medicine, 6(2), 3.

Klareskog, L., Stolt, P., Lundberg, K., Kallberg, H., Bengtsson, C., Grunewald, J., . . . Alfredsson, L. (2006). A new model for an etiology of rheumatoid arthritis: smoking may trigger HLA-DR (shared epitope)-restricted immune reactions to autoantigens modified by citrullination. Arthritis Rheum, 54(1), 38-46. doi:10.1002/art.21575

McInnes, I. B., & Schett, G. (2011). The Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis. The New England Journal of Medicine, 365(23), 2205-2219.

Smolen, J. S., Aletaha, D., Koeller, M., Weisman, M. H., & Emery, P. (2007). New therapies for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. The Lancet, 370(9602), 1861-1874. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(07)60784-3